Soleares (plural of soleá, pronounced [soleˈa])

One of the basic forms of flamenco or palos of Flamenco music, probably originating among the Calé Romani people of Cádiz or Sevilla in Andalusia. Soleares refer to “mother of palos”, although it is not the oldest one and not even related to every palo (as fandangos, which is from a different origin)

It is usually accompanied by one guitar only, in phrygian mode “por arriba” (fundamental on the 6th string), or for instance, “Bulerías por Soleá” is usually played “por medio” (fundamental on the 5th string).

The melody of a soleá stanza usually stays within a limited range (usually not more than a 5th). Its difficulty lies in the use of melisma and microtones, which demand great agility and precision in the voice. It is usual to start a series of soleares with a more restrained stanza in the low register, while continuing to more and more demanding ornaments in a higher register. The series is quite often finished with a stanza in a much more vivid tempo in the relative Major mode.

Main Soleá styles

- Soleares from Alcalá

- Soleares from Triana

- Soleares from Cádiz

- Soleares from Jerez

- Soleares from Lebrija

- Soleares from Utrera

Structure of the Soleá form

Soleá guitar style is easily identified by its metre and Phrygian mode, but also by a series of characteristic phrases. A guitarist, when playing soleá, will combine:

- “llamadas” (the “call”) on the I degree of the Phrygian altered cadence (in E, E major)

- “compas” (the standard accompaniment figure)

- “falseta” (plur. “falsetas”), melodic ideas played between different stanzas.

All sections have an even number of “compas” and are comparable in duration.

Compás

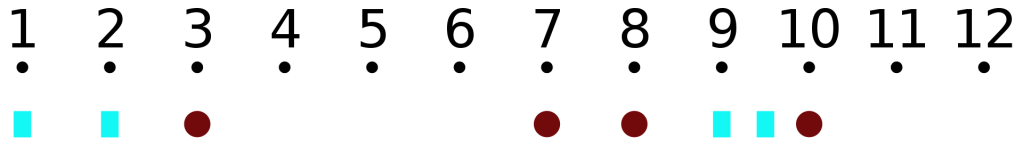

The metre or “compás” of the soleá is one of the most widely used in Flamenco. Other palos have derived their compás from the soleá, including Bulerías por soleá, the palos in the Cantiñas group, like Alegrías, Romeras, Mirabrás, Caracoles or, to a certain extent, Bulerías. It consists of 12 beats, and could be described as a combination of triple and duple beat bars, so it’s a polymetre form, with strong beats at the end of each bar. The basic “skeleton” of the soleá rhythm, thus, follows this pattern:

(Each number represents a beat. Blue squares mean weak beats, while big brown dots are strong beats.)

Nevertheless, this is just an underlying structure, like a foundation, a kind of grid where flamenco artists creatively draw the rhythm by means of subdivisions, articulation, and less commonly, syncopation and accent displacement.

The first example of “palmas” is a very common, simple pattern:

Notice that palmas are often (though by no means always) silent during beats 4 to 6, even if beat number 6 is a “strong one”. This is specially true when no dancing takes place: the main interest there is the singing (or playing) and too much percussion can take attention away from the music. Those beats though are often marked when there is dance, or when performing other palos in the same metre like Alegrías or Bulería por soleá. However, these are not to be taken as hard-and-fast rules, but just as general guidelines.

A basic solea rhythm played with cajon and palmas. The compas of solea starts on the “one” count and accents the 3, 6, 8, 10, and 12 beats of the 12 beat cycle.

Solea is a palo that can accommodate quite a bit of “push and pull” tempo-wise. This doesn’t, however, mean the count changes: be sure not to drop beats or “add 13s.”

3 thoughts on “Soleá”